We've all been there—trapped in a meeting that seems to go on forever, watching precious time slip away while discussions meander aimlessly and nothing gets accomplished. Joseph Grenny from the HBR Guide to Making Every Meeting Matter shares a powerful personal story about sitting in traffic school, watching the instructor arrive 25 minutes late and realizing by 8:15 that he was only on slide 18 of 123. That toxic sense of dread and powerlessness he felt mirrors exactly what happens in countless business meetings every day. The crucial insight, however, is that most participants act like passive victims rather than responsible actors who can change the meeting's trajectory.

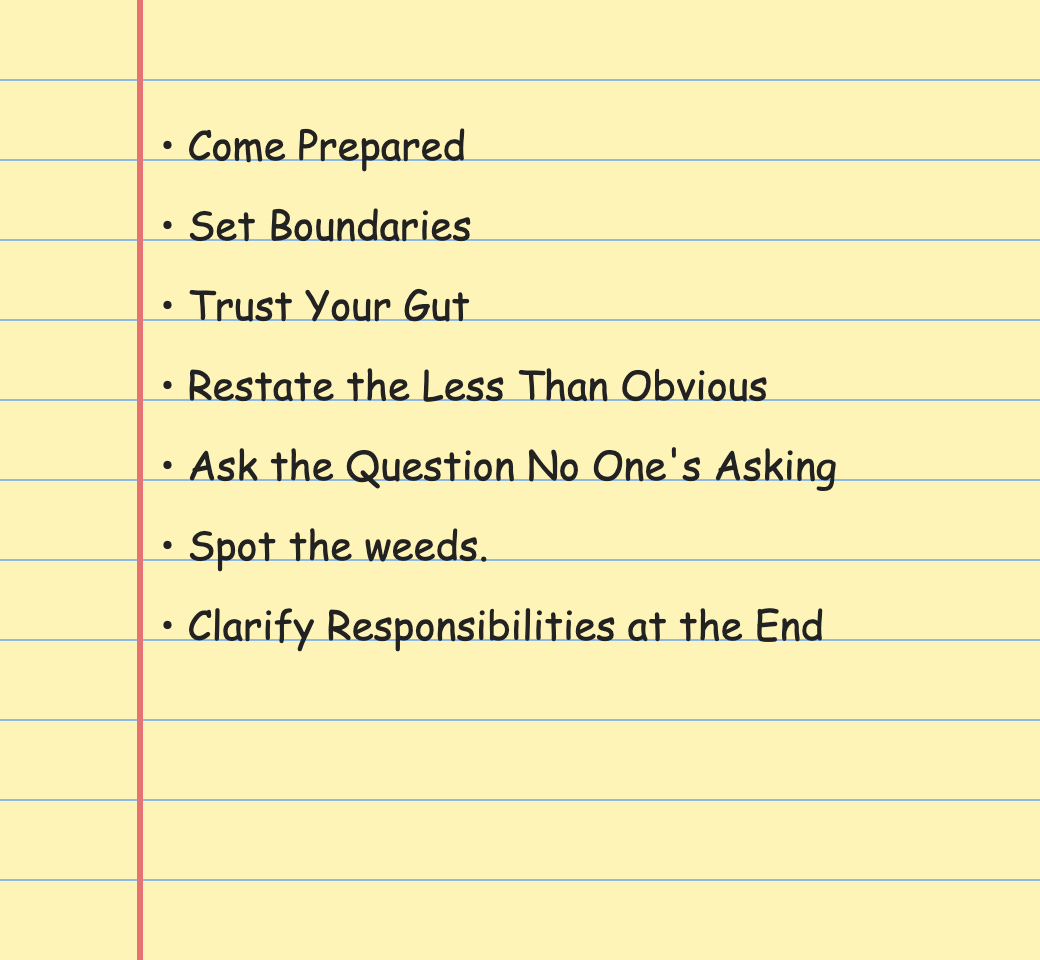

The good news is that you have far more power than you realize to stop meetings from dragging on. When you're suffering in a meeting, others are likely suffering too, and it's within your power to do something about it. Most people silently cheer when someone takes action to refocus or cut off time-wasting activities. Throughout this lesson, you'll discover seven tactical interventions that can transform you from a passive victim into an active agent of meeting efficiency.

Understanding the root causes of unproductive meetings is the first step toward fixing them. There are three main culprits that turn potentially valuable meetings into time-wasting frustrations.

- Misunderstood Purpose: When participants arrive with different expectations—some to decide, others to inform, and others to brainstorm—the conversation fragments and progress stalls. This confusion often comes from vague agendas or unclear invitations.

- Passive Participation: Meetings drift when attendees don’t actively engage. Researchers have found that this bystander mentality is especially common in larger groups, where everyone assumes someone else will step in to keep things on track.

- Leaders Constrained by Imaginary Rules: Meeting leaders often hold back from redirecting or cutting off unproductive discussion, fearing it will seem rude or go against group expectations. In reality, most participants are hoping someone will step in to make the meeting more effective.

These factors reinforce each other, leaving no one empowered to address obvious problems. The larger the meeting, the more diluted individual responsibility becomes. Recognizing that most meeting dysfunction stems from shared passivity rather than active choices shows that even small interventions can have a big impact.

The battle against meandering meetings is often won before anyone enters the room. Taking responsibility for meeting productivity starts with your own preparation. One of the most effective strategies is to come prepared with a clearly articulated position on the topic. This doesn’t mean dominating the conversation, but rather offering a structured starting point if the discussion becomes unfocused. Phrasing it as, “Would it be helpful if I shared a possible approach to get us started?” provides value to the group and helps organize everyone’s thinking.

Equally important is to set boundaries and communicate your time constraints at the start of the meeting. For example, saying, “I have a hard stop at 10:45,” creates urgency, signals respect for everyone’s time, and gives you a graceful exit if the meeting drags on. This not only models good time management but also encourages others to be more mindful of the agenda and timing.

By preparing thoughtfully and setting clear boundaries, you position yourself as a positive force for focus and efficiency. These simple steps can inspire others to engage more productively and help prevent meetings from expanding to fill more time than necessary.

When a meeting starts to go off track, you can use several intervention tactics that help refocus the group without coming across as rude. These techniques focus on the collective good and invite group participation in improving the meeting’s effectiveness:

- Spot the Weeds: Gently call out when the discussion drifts into unnecessary detail or unrelated topics. Suggest handling "wordsmithing" or deep dives offline or in a smaller group.

- Trust Your Gut: If you’re feeling lost or confused, voice it tentatively and invite others to share if they feel the same. Framing it as a question (“Are others seeing this too?”) helps the group acknowledge and address the issue.

- Restate the Less Than Obvious: Summarize what’s actually being discussed or decided to help the group refocus and avoid conflating separate issues. An example, "I'm hearing points about both whether this is a good investment and when we should make the purchase. I think we've already made the purchase decision and timing is the only question. Is that right?"

- Ask the Questions No One Else Is Asking: Surface unspoken concerns or “elephants in the room” by asking for confirmation of issues that seem to be lingering beneath the surface.

- Clarify Responsibilities at the End: Summarize decisions and next steps so everyone leaves with clear commitments and accountability. It typically takes just a minute, but it can prevent hours of confusion and avoidable follow-up meetings.

Using these interventions, you can help transform an unproductive meeting into a focused and productive one, all while supporting the group’s success.

Let's see how these intervention tactics work in practice during a typical team meeting that's starting to go off the rails:

- Victoria: I’m sorry to interrupt, but I’m not sure I’m following. We seem to be jumping between vendor selection and the approval process. Are others seeing that too?

- Dan: Good point. I thought we were here to choose between the three vendors we’ve already vetted.

- Victoria: That’s what I thought as well. Maybe we can focus on the selection criteria now, and handle the approval process separately? And before we wrap up, can we quickly summarize who’s responsible for what so we’re all clear on next steps?

- Dan: Sounds good. Let’s do that.

Notice how Victoria uses multiple intervention tactics seamlessly: she trusts her gut to voice confusion, restates the less obvious by clarifying what decision they're actually making, spots the weeds by redirecting from procurement process details, and sets up the expectation for clarifying responsibilities at the end. Her interventions are framed as serving the group's interests, not as criticism, which makes them well-received by her colleagues.