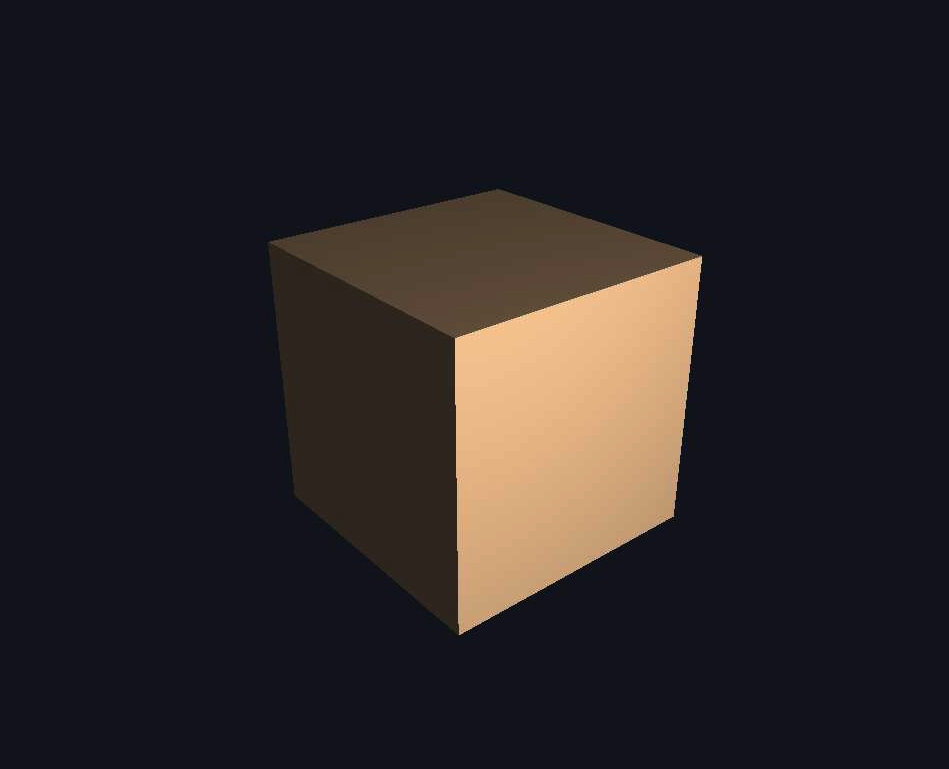

Welcome back to the third lesson of Realistic Lighting with the Phong Model! In our previous lesson, we successfully implemented ambient lighting, creating uniform illumination that gently bathes our 3D cube in soft, even light. Now we're ready to add the next fundamental component: diffuse lighting. While ambient lighting provides uniform base illumination, diffuse lighting creates the directional shading that makes objects appear truly three-dimensional. This lighting component responds to surface orientation, making faces that directly face our light source appear brighter, while those angled away become progressively darker. By the end of this lesson, we'll transform our uniformly lit cube into a realistically shaded object that clearly reveals its three-dimensional form through proper directional lighting.

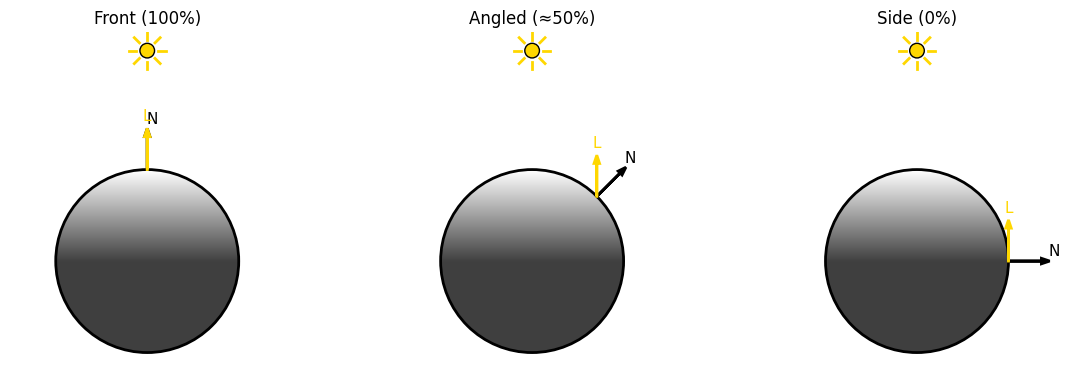

Diffuse lighting represents the way rough, matte surfaces scatter incoming light in all directions, creating the fundamental shading that reveals an object's three-dimensional form. Unlike the uniform ambient lighting we implemented previously, diffuse lighting depends entirely on the angle between the surface and the light source. When a surface faces directly toward the light, it receives maximum illumination; as the surface turns away, the illumination decreases smoothly until surfaces perpendicular to the light receive no diffuse contribution at all. This behavior follows Lambert's cosine law, a fundamental principle in physics that describes how the apparent brightness of a perfectly diffusing surface varies with the viewing angle. In computer graphics, we simulate this natural phenomenon using the mathematical relationship between surface normals and light direction vectors.

The core of diffuse lighting lies in a simple yet powerful mathematical concept: the between the surface normal and the direction toward the light source. This dot product gives us the cosine of the angle between these two vectors, which directly corresponds to the intensity of diffuse illumination.