Welcome back to Interactive Camera and Texturing! We've reached lesson 3, marking significant progress in our journey through interactive 3D graphics. In our previous lessons, we built a robust camera system that responds to both movement and look controls, allowing us to navigate through 3D space with complete freedom. Now, we're ready to take the next major step: bringing our 3D scenes to life with textures. Texturing transforms plain geometric surfaces into visually rich objects that can represent real-world materials, patterns, or artistic designs. Today, we'll learn how to load external images, apply them to 3D geometry, and integrate texture mapping seamlessly with our existing camera system to create compelling visual experiences.

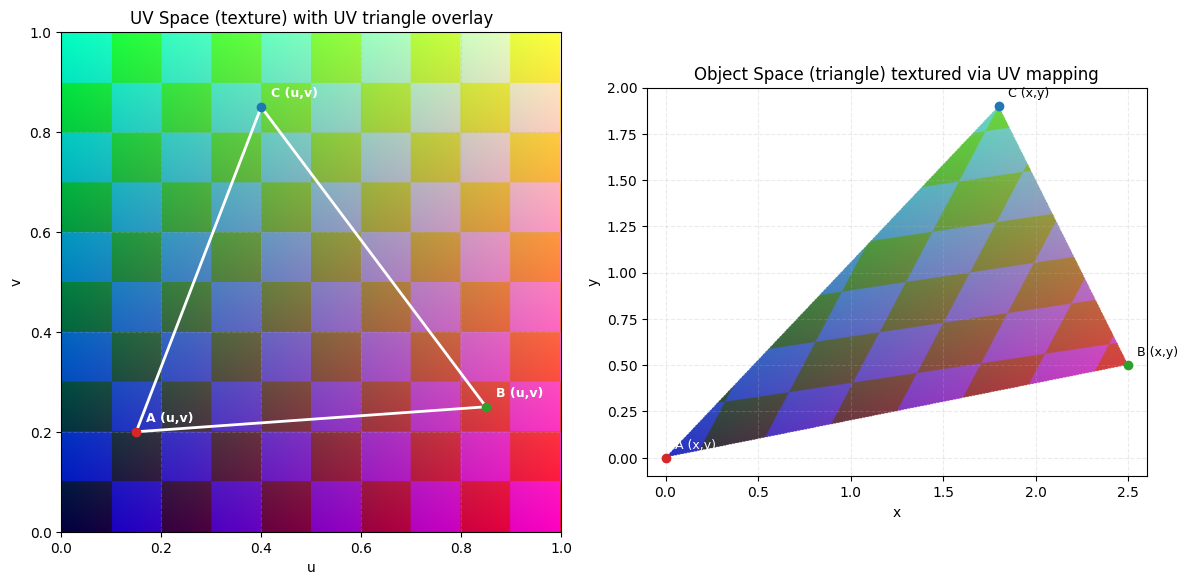

Texture mapping is the process of applying 2D images onto 3D surfaces to create the illusion of detail and material properties. Think of it like wrapping a photograph around a box: the image gets stretched and positioned to cover the geometric surface. In computer graphics, we accomplish this through UV coordinates (also called ST coordinates), which create a mapping between 2D image pixels and 3D surface points. The term UV represents the coordinate system of the texture image, where U is the horizontal axis and V is the vertical axis. They are labeled this way to avoid confusion with other coordinate axes. These coordinates typically range from 0.0 to 1.0, where (0,0) represents the bottom-left corner of the image and (1,1) represents the top-right corner. By assigning UV coordinates to each vertex of our geometry, we tell the GPU exactly how to stretch and position the texture across our 3D surfaces.

To enable texture mapping, we must expand our vertex data to include UV coordinates alongside position information. Previously, our vertex data included RGB color values for each vertex to specify its color. Now, we replace those RGB values with UV coordinates, which will be used to map the texture image onto the geometry. Our enhanced vertex array now contains five values per vertex:

Each vertex now includes three position values (X, Y, Z) followed by two UV values (U, V). For the front face, notice how the UV coordinates form a square mapping: bottom-left (0,0), bottom-right (1,0), top-right (1,1), and top-left (0,1). This creates a direct correspondence between the texture image and the face geometry, ensuring the image appears correctly oriented on the surface.

Our vertex attribute setup must accommodate the additional UV coordinates by updating both the stride and adding a second attribute pointer:

The key changes are the stride parameter of 5 * sizeof(float) and the new UV attribute at location 1. The stride tells OpenGL that each vertex occupies five float values in memory. The UV attribute pointer starts at offset 3 * sizeof(float), skipping over the three position values to reach the UV coordinates. This setup allows the GPU to correctly interpret our interleaved vertex data.

Our vertex shader requires updates to receive UV coordinates from the vertex data, as defined in the attributes, and then pass them to the fragment shader:

The vertex shader now accepts UV coordinates through the aUV input attribute and passes them unchanged to the fragment shader via the vUV output variable. This interpolation process means that UV coordinates get smoothly blended across triangle surfaces, allowing the GPU to determine the correct texture coordinate for every pixel, not just at vertices.

The fragment shader performs the actual texture lookup using the interpolated UV coordinates:

This shader uses the texture() function to sample the bound texture at the specified UV coordinates. The sampler2D uniform represents our texture object, while the vUV coordinates determine which pixel from the texture image to retrieve. The GPU automatically handles texture filtering and interpolation between pixels, creating smooth visual results even when the texture resolution differs from the screen resolution.

Now that we've prepared our shaders to handle texture sampling, we need to load actual image data from files. This is where the stb_image library becomes essential, providing cross-platform image loading capabilities that work seamlessly with OpenGL.

To use stb_image for loading textures, download stb_image.h and add it to your project. In one source file, define STB_IMAGE_IMPLEMENTATION before including the header:

In other files, just include the header normally. This setup lets you use stb_image functions like stbi_load and stbi_image_free for image loading and management.

With the stb_image library set up in your project, you’re ready to load image files and prepare them for use as textures in OpenGL. The stb_image library supports a wide range of image formats (such as JPEG, PNG, BMP, and more) and provides a simple interface for reading pixel data directly into memory. This makes it easy to integrate external images into your graphics pipeline, allowing you to texture your 3D objects with any image you choose.

Because OpenGL expects textures with (0,0) positioned at the bottom-left corner while most image formats store pixels with (0,0) at the top-left, we begin by calling stbi_set_flip_vertically_on_load(true) to resolve this coordinate system difference. We then load the image data using the stbi_load function, which automatically detects the image format and provides us with the width, height, and channel count. The resulting data contains raw pixel values ready for transfer to GPU memory.

With our image data loaded, we create an OpenGL texture object and configure its behavior:

The texture parameters control how the GPU handles edge cases and rendering quality: GL_REPEAT causes the texture to tile when UV coordinates exceed the 0-1 range, while GL_LINEAR filtering provides smooth interpolation between pixels for both minification and magnification. The glTexImage2D call uploads our image data to GPU memory, and glGenerateMipmap creates additional mipmap levels for potential future use or different filtering configurations.

During our render loop, we must bind the texture and set the appropriate uniform before drawing:

Here, texLoc is obtained by calling glGetUniformLocation(shaderProgram, "uTexture"), which retrieves the location of the uTexture uniform defined in the fragment shader. This allows us to set the correct texture unit for sampling in the shader. The glActiveTexture(GL_TEXTURE0) call selects texture unit 0 as the active unit, while glBindTexture associates our texture object with that unit. The uniform value of 0 tells the shader to sample from texture unit 0. This system allows us to use multiple textures simultaneously by binding them to different texture units.

When we run the application, we see our familiar cube transformed. Instead of a plain colored surface, we now see a fully textured cube with the image mapped across all six faces. We can navigate around it using our established WASD movement and arrow key look controls, experiencing how the texture appears from different angles and distances. The integration demonstrates how texturing enhances our existing 3D systems without disrupting the underlying functionality.

The result is a photogenic face applied to our 3D object, showcasing the power of texture mapping in bringing geometric surfaces to life.

We've successfully integrated texture mapping into our 3D graphics pipeline, transforming simple geometry into visually compelling surfaces. Our implementation covers the complete texture workflow: loading external images with stb_image, configuring UV coordinates for proper mapping, updating shaders for texture sampling, and integrating everything with our existing camera system. The result is a robust foundation that combines interactive navigation with rich visual detail, demonstrating how different graphics systems work together to create engaging 3D experiences.

The textured camera system now provides a complete platform for creating immersive visual applications, where users can explore detailed environments with full freedom of movement and orientation. It's time to put these texture mapping concepts into practice through hands-on exercises that will solidify your understanding and help you master the art of bringing visual life to your 3D worlds!