Welcome to Avoid Bias in Critical Thinking! Understanding biases isn't about eliminating them completely—that's impossible since we're all human. Instead, it's about becoming aware of them so you can manage their influence on your thinking and decisions.

In this lesson, you’ll learn:

- What a bias is, in simple terms

- How to recognize three common types of bias in everyday situations

- Ways these biases can shape what you believe or choose

These skills will help you in daily life, whether you’re making a personal decision or working with others.

A bias is like a shortcut your brain takes to help you make quick decisions. Your mind is always trying to save time and energy, so it uses your past experiences, feelings, and beliefs to make sense of new information. Sometimes, these shortcuts are helpful. But other times, they can lead you to see things in a way that isn’t completely fair or accurate.

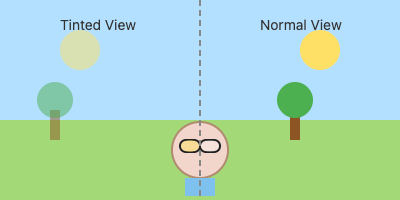

Think of it like wearing sunglasses with colored lenses. Everything you see is tinted by the color of the glasses, but after a while, you forget you’re even wearing them. Biases work in a similar way because they color how you see the world, often without you noticing.

For instance, if you’ve always had good experiences with a certain type of food, you might automatically think it’s the best, even if you haven’t tried other options. Or, if you’ve heard a lot of stories about something going wrong, you might believe it’s more common than it really is.

The important thing to remember is that everyone has biases. You can’t get rid of them completely, but you can learn to notice when they might be affecting your thinking. When you’re aware of your biases, you can pause and ask yourself, “Am I seeing the whole picture?” or “Could I be missing something?” This helps you make better, more thoughtful choices.

Let’s look at three common types of bias you might notice in your daily life:

1. Confirmation Bias

This is when you pay more attention to information that matches what you already believe, and ignore or downplay information that doesn’t. For example, if you think a certain exercise is the best way to get fit, you might notice every article or video that agrees with you, but skip over anything that suggests a different method.

2. Anchoring Bias

This happens when the first piece of information you hear about something sticks in your mind and affects your later decisions. Take this situation: you see a jacket on sale for $100, and then see another one for $70. The second one seems like a great deal even if $70 is still more than you wanted to spend. The first price you saw becomes your “anchor.”

3. Availability Bias

This is when you think something is more common or important just because it’s easy to remember. Imagine you recently heard about a few people catching a cold, and you start to think, “Everyone is getting sick right now!” even if most people around you are healthy. Your brain uses the examples that come to mind first, even if they aren’t the whole story.

Here’s how these biases might show up in a conversation:

- Marcus: I've been thinking about switching to freelance work, but it seems way too risky.

- Natalie: Why do you think it's so risky?

- Marcus: My friend tried it once and said it was tough. Plus, I read an article that said most people give up quickly.

- Natalie: Do you know anyone who stuck with it and enjoyed it?

- Marcus: Actually, yeah, my neighbor does pretty well... but she's probably just lucky. Most people fail at it.

In this example, Marcus is focusing on stories that match what they already believe (confirmation bias), letting the first thing they heard set their expectations (anchoring bias), and thinking that freelance work is hard just because that’s what comes to mind first (availability bias).

These mental shortcuts can make you feel more confident in your opinions, even if you don’t have all the facts. Biases can also limit your options without you realizing it. If you let the first thing you hear (anchoring bias) or the stories that are easiest to remember (availability bias) guide your decisions, you might overlook better choices or make unfair judgments about people and situations. By noticing when these biases might be at work, you can pause, ask more questions, and make decisions that are more balanced.