When you've assembled your cross-functional team and clarified the business need, it’s tempting to run with the first good solution. However, the HBR Guide to Building Your Business Case by Raymond Sheen makes it clear that stakeholders expect evidence of thorough analysis, not just acceptance of the obvious answer. Even if there’s a front-runner idea—perhaps from your CEO or an approach that is common in your industry—you need to show you’ve seriously considered multiple options.

Generating and evaluating alternatives is not just a box-checking exercise. It’s a critical thinking discipline that often reveals better solutions or helps you defend your preferred one. Sometimes the second or third option is faster, cheaper, or less risky. In other cases, exploring alternatives helps you understand and justify your recommendation.

In this lesson, you’ll learn techniques for generating creative alternatives, including the essential do-nothing option. You’ll see how to evaluate the real cost of inaction, a powerful tool for creating urgency. Finally, you’ll learn to narrow your possibilities to two or three genuinely viable choices, avoiding the trap of offering obviously inferior options just to make your preference look good.

When brainstorming solutions, let your team think out loud without constraints at first. Briefly describe the pain, who’s feeling it, and its cause, ensuring that it is just enough to orient the group. Then ask for suggestions, including any ideas stakeholders proposed early on, and challenge your team to generate more possibilities.

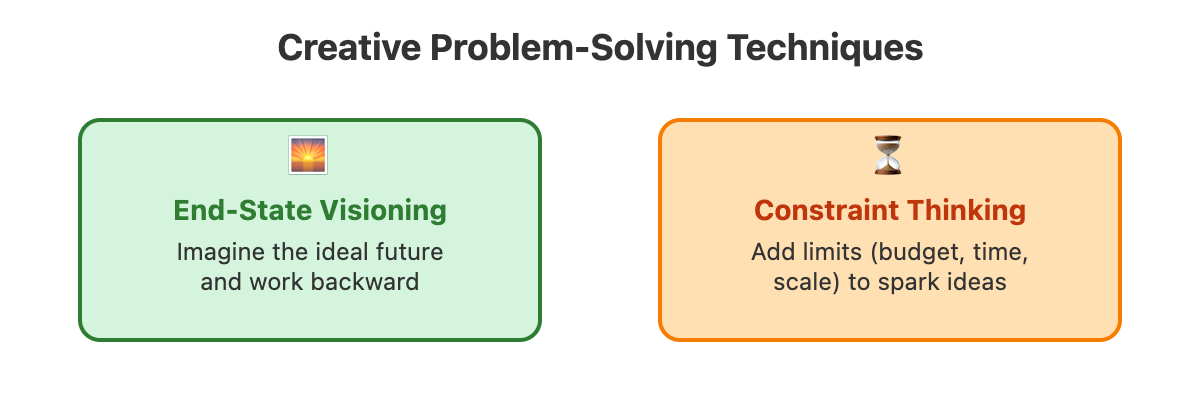

When your team gets stuck on the obvious solution, two techniques can help: End-state visioning and constraint-based thinking.

End-state visioning asks you to imagine the ideal future state and work backward. Instead of "How do we fix our inventory system?" ask, "What would perfect inventory management look like?" This often unlocks creative thinking and reveals solutions you might not have considered.

Constraint-based thinking introduces limitations to spur creativity. Explore scenarios with different parameters: What if you had half the budget? Twice the time? Needed to scale to 100 times the volume? These constraints force your team to abandon conventional thinking.

For example, two managers working on customer service improvements might use constraints like these:

- Jessica: Everyone keeps coming back to hiring more reps, but that’s $2 million annually.

- Ryan: What if we only had $1 million?

- Jessica: Then we could only hire five reps. That won’t solve the problem.

- Ryan: What else could we do with $1 million?

- Jessica: Maybe invest in self-service tools, like an AI chatbot.

- Ryan: What if we had only 30 days to implement?

- Jessica: We could partner with an outsourcing firm that already has trained reps.

- Ryan: What if we had to handle 10 times our current volume?

- Jessica: We’d need automation or maybe community support forums.

Each constraint led to new alternatives beyond simply hiring more people.

Another approach is to consider how different departments would solve the problem. IT might suggest automation or new software tools, HR might focus on enhanced training programs or process changes, and finance might propose supplier penalties or incentive structures. Involving these diverse perspectives can reveal viable alternatives you might not have considered, or highlight elements from each approach that could be combined into a stronger solution.

One essential concept in business case analysis is the "do-nothing" option, or explicitly considering what happens if no action is taken. In many organizations, sticking with the status quo is the default, whether due to risk aversion, competing priorities, or lack of urgency. That’s why it’s important to go beyond evaluating proposed solutions and also analyze the impact of inaction. A business case should answer not only, "What happens if we take this action?" but also, "What happens if we don’t?" This analysis is a powerful tool for articulating the business need and creating urgency. By quantifying the risks, costs, and missed opportunities associated with doing nothing, you help stakeholders see that inaction is itself a decision with real, often escalating, consequences.

For example: "If we stick with our current line, sales will continue to drop 10% a year. This new product will reverse that trend. In fact, we project a 20% increase in sales over the next five years." This comparison makes the case for action clear. Without this analysis, stakeholders might assume maintaining the status quo is free, when in reality, doing nothing often carries significant and escalating costs.

To evaluate the "do-nothing" option, project current trends forward with specificity. If customer complaints are rising 15% quarterly, where will they be in two years? If you’re losing market share, when will you drop below sustainable levels? These projections help stakeholders see that the choice is not between spending and saving, but between strategic investment now and forced, reactive spending later.

Sometimes, doing nothing is a viable option, especially for internal improvements. If the costs of inaction are manageable, stakeholders may choose to absorb them. Your role is to ensure they make that choice with full knowledge of the consequences.

When presenting the "do-nothing" option, be specific. Instead of saying, "Things will get worse," provide concrete projections, such as, "System downtime will increase from 4 to 12 hours monthly within 18 months, costing $75,000 per month in lost productivity and emergency repairs." This detail helps stakeholders grasp the real impact of inaction.

After generating alternatives and analyzing the "do-nothing" option, you must present the right number of choices. Be wary of both extremes: one option feels like railroading, but too many options overwhelm. The sweet spot is two or three reasonable choices beyond the "do-nothing" option.

To narrow your options, use filtering questions: Which costs least? Which is fastest to implement? Which carries the fewest risks? Which generates the most revenue? Each alternative you present should have at least one significant advantage.

Your champion provides insider knowledge to help you refine your choices and frame them for the review committee. They might share insights like, "The CFO won’t approve anything over $3 million," or "The board wants results before the next earnings call." This helps you select and present the most relevant options.

Subject-matter experts provide reality checks. An option that looks good on paper may be impractical due to technical or supplier constraints. If an option is impossible or unacceptable, modify or drop it.

During financial analysis, one alternative often emerges as the clear winner. Still, present the other viable options to show your analytical thoroughness. If you rejected alternatives, explain why: "We considered outsourcing, which would save $2 million annually, but rejected it due to security concerns and an 18-month transition period." This transparency demonstrates thorough analysis and helps stakeholders understand your recommendation.

Finally, consider recent business events when selecting which alternatives to present. If your company recently had a negative experience with consultants, don’t lead with a consultant-heavy solution. If there’s a push for automation, ensure at least one alternative emphasizes that. You’re not changing your analysis to match politics, but being thoughtful about which valid alternatives deserve the spotlight given the current context.

In your upcoming role-play exercises, you’ll experience firsthand the challenge of generating creative alternatives, building a compelling "do-nothing" analysis, and selecting the right options to present to different stakeholders with varying priorities and concerns.